This month’s reading picks from the Caribbean, with reviews of Wild Fires by Sophie Jai; Uncertain Kin by Janice Lynn Mather; let the dead in by Saida Agostini; and The Most Magnificent! by Jeunanne Alkins and Neala Bhagwansingh

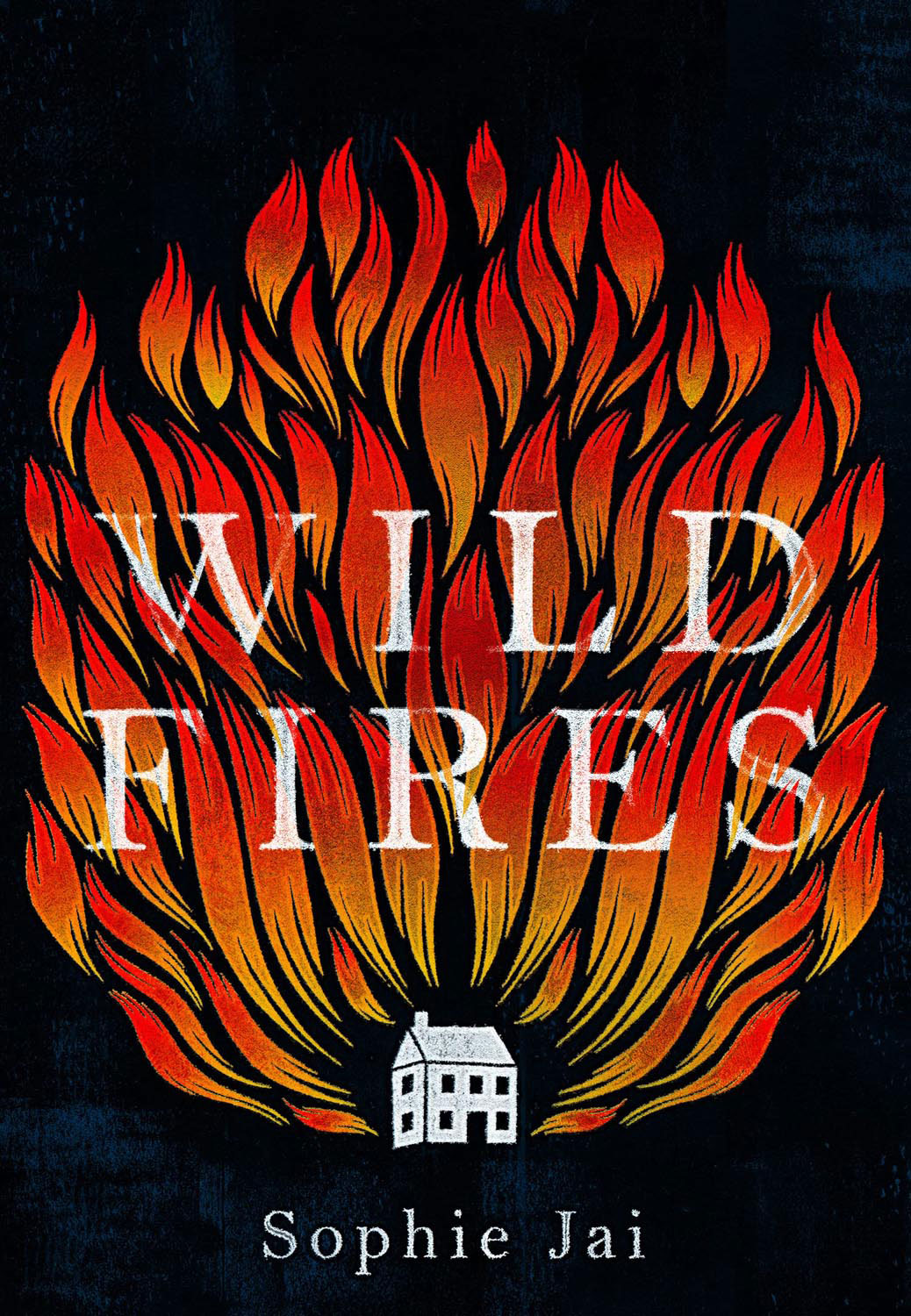

Wild Fires

by Sophie Jai (The Borough Press, 320 pp, ISBN 9780008380342)

Don’t be surprised if more secrets than salvation greet you in grief’s waiting room: this reality awaits Cassandra, Wild Fires’ central character, who journeys to her family home to attend a funeral. In life, her cousin Chevy was mute: in death, the space left by his passing resounds with echoes of the unanswered, the nebulous, and the unasked. Less a procedurally plotted investigation of domestic drama, Jai’s debut concerns itself with the underpinnings that both inhabit and haunt any clan of people bound by blood. In the peregrinations struck between Trinidad and Canada, vaulting between dusty decades and difficult decisions, this debut cuts through the undergrowth of lies we tell ourselves to preserve the peace. Cassandra, weaving her way through the minefield of visiting relatives’ acid-laced reminiscences, is a sensitively wrought figurehead for this discovery: a redoubtable anti-heroine.

Uncertain Kin

by Janice Lynn Mather (Doubleday Canada, 304 pp, ISBN 9780385697156)

Is there a liminal state, a threshold when a Caribbean girl becomes a woman? If so, the 18 interwoven short stories of Uncertain Kin possess that space with passionate inquiry. Across the islands of The Bahamas, these protagonists seize life, or have it stripped from them: from so many perches, a hypervigilant grandmother sits, surveying everything that passes. In “Mango Summer”, hog plum mangoes lose their ubiquitous sweetness all too soon, their richness souring against the sorrow of a beloved sister’s disappearance in the dead of night. Mather opens wide the doors of synaesthetic perception: colours blend into sounds, and tastes of the Bahamian palate burst in the mind’s eye. All are implicated in these coming of age, or loss of innocence narratives: straddling disenchantment and delirium, the final surge of meaning in these short fictions is fundamentally feminist.

let the dead in

by Saida Agostini (Alan Squire Publishing, 68 pp, ISBN 9781942892281)

The Pomeroon River in Guyana is that vast country’s deepest: to witness it channelled in the poems of Saida Agostini is to glean an appreciation for this debut collection’s intense fathoms. Tracing lineages from the Essequibo’s forest-fringed banks to the frigidity of winter in Maryland, Agostini charts fraught emotional waters with the heart’s astrolabe. You won’t find flippant references to family trees herein: the approach of the poems is mycelial, a mushrooming network of ties that bind, snap, and resolder themselves across generations. What emerges is poetry as fierce, fundamental witness: repeatedly, the speakers of these verses ask, Where can pleasure and purpose be found for the fat Black queer woman’s body in this world? The echoing answers are a spiral of reclamations, voices reaching backwards to the past, forward to the future, for outrageous hope.

The Most Magnificent!

by Jeunanne Alkins and Neala Bhagwansingh (Everything Slight Pepper, 42 pp, ISBN 9789769535053)

What stories might our oldest buildings tell, if they could speak? Co-writing team Alkins and Bhagwansingh answer this question for architectural enthusiasts in The Most Magnificent!, a whimsy-laced, pedagogical whirl through the histories and significances of the seven stately structures that flank Trinidad & Tobago’s Queen’s Park Savannah. Sayada Ramdial’s accompanying illustrations exclaim as much as the text does, infusing this story of built heritage with a playfulness that almost feels interactive. Alkins’ mission in storytelling for juvenile readers has long been to balance breath-taking design with educational excitement: this production is the crowning jewel of her publications to date. It’s no mean endeavour, either: anthropomorphising history can be tricky, but in these pages, Stollmeyer’s Castle morphs into Sir Stollmeyer, wise and jovial: who can argue with a castle regaling you with his provenance?