“The Soenil Revolution” was how Food Inspiration Magazine, an online publication for professional chefs, put it. Soenil Bahadoer’s unique gastronomic creations have been causing gourmands from all over Europe — and beyond — to beat a path to his two-Michelin-starred Restaurant De Lindehof, in the far-flung Dutch village of Nuenen.

Trained in classic French cuisine under legendary chefs in Belgium, France and Holland, Soenil has become awash in culinary awards since he began incorporating elements from his Surinamese background into his dishes.

Reviewers rave about the delicate spiciness he has injected into European haute cuisine. In the Netherlands, he was named an SVH Meesterkok (or Masterchef) in 2015. In 2021, he placed 58th in the international Best Chef Awards. And the Gault & Millau guide rates De Lindehof a score of 17 out of 20, also naming Soenil Chef of the Year in 2020.

“Classic French cuisine is and always will be exquisite,” he says. “But at a certain point in my career I got tired of the inevitable duck a l’orange. I don’t feel at home in rigidly measured recipes, with rules and instructions. Feeling! That’s what my kitchen is all about. What I do is to search for the flavours. I want them to be more intense. They must touch you.”

This devotion to emotion runs through all his conversation. “Cooking is about making contact,” he says.

In contrast to the celebrated TV “masterchefs” swearing and sweating in testosterone-fuelled cooking contests, Soenil sees food in terms of warmth and comfort, family and community. Diners praise the atmosphere of hospitality he creates at De Lindehof, receiving guests at the door himself and helping to bring dishes to their table.

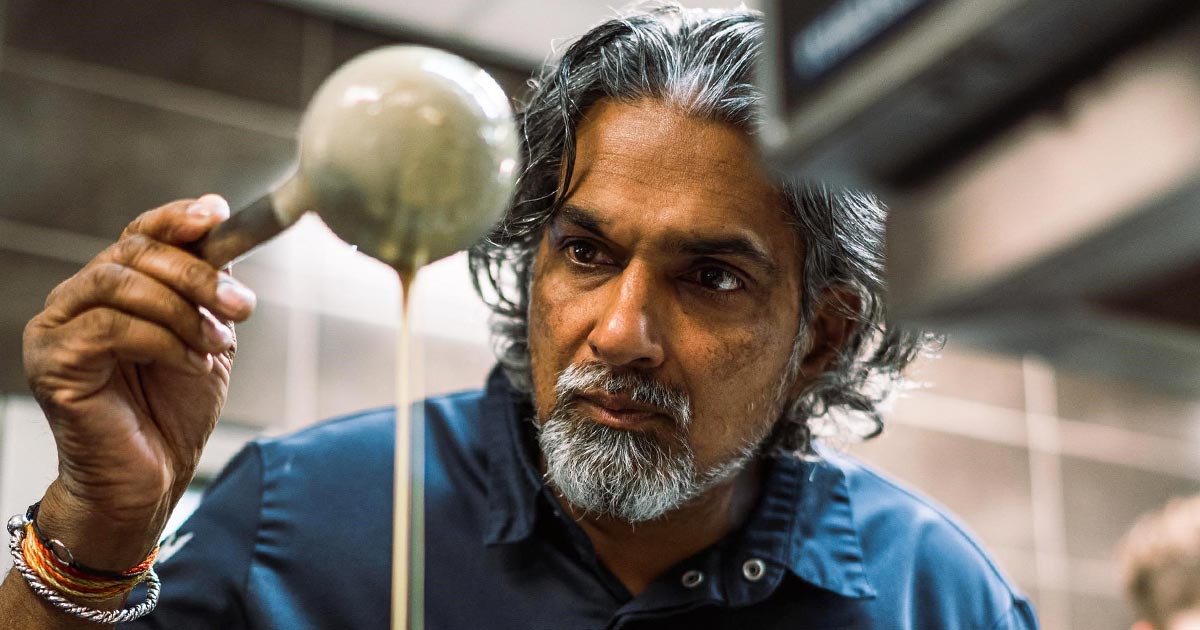

This seems part of the Caribbean persona he has clung to with his mop of tousled curls, grey jeans and sneakers under his chef’s jacket. Like his menu, he is a medley: intense but relaxed, boisterous as well as business-like, spontaneous yet reflective.

“The key to cooking is to find balance and harmony,” he says.

“Balance” seems to be his favourite word. He is constantly negotiating tradition and innovation, experiences and tendencies, spontaneity, and the striving for perfection.

“We have seven cultures in Suriname, and 13 Indigenous groups…” His eyes widen in wonder. “And all these flavours mix…”

At De Lindehof, he uses this vast range of tradition and technique to weave an epicurean tapestry threaded through with hints of ancient tropical flavours. Amuse-bouche follows amuse-bouche between courses, each one a delicate combination of shapes, colours and flavours — starters like king crab with caviar and phulauri (phulourie); and main courses like lobster with okra chutney and bitter melon.

But when asked what his own favourite food is, he opts for the simplest and most traditional.

“My mother’s roti,” he says. “Home food is the best.”

He learned to cook from her, he says. And she still drops by the restaurant regularly to check up on him.

“As a child, when I was naughty, my mother used to put me under house arrest. She used to plonk me in the kitchen while all other children were outside playing. So I began watching how she ground different spices to make masala, and developed a knowledge of the different scents and effects.”

He speaks often about his years as a child in rural Suriname, his hard work and beloved family. His family migrated to the Netherlands when he was eight. Until then, he and his four siblings walked 10 miles to and from school and had to help on their parents’ farm when they got home.

But his reminiscences about those days contain a kind of joy at the richness of his experiences. He speaks about his father going hunting in the forest and fishing in the rivers of South America. You sense that this is what gave him a kind of pure appreciation of different food items, of what is fresh and natural and straight from the source.

“We lived in my grandmother’s house,” he says. “The women used clay from the river behind the house to make an oven, and cooked fish from the river with spices in a big cast-iron pan. You never forget the fragrance of that cooking.”

Till today, he has ingredients and spices flown in from Suriname on a weekly basis.

“When I spot a mango,” he wrote in his book Spicy Chef, “good manners go out of the window. You just eat it with your hands, tear off the skin with your teeth and knock yourself out.”

During the Coronavirus restrictions, when restaurants couldn’t open, Soenil couldn’t just sit on his hands. He designed an up-market food truck and sold snacks on the street. People came all the way from Germany and lined up for two hours for his baras (“buns” made Surinamese-style with lentil-based flour) filled with Wagyu beef and black truffles.

“They cost 65 euros each,” says Soenil. “But at least people who couldn’t afford to come to the restaurant could enjoy what we had to offer.” A six-course meal at his restaurant runs nearly 275 euros per person.

The food truck was featured on the Dutch television evening news, with Soenil and his party of chefs doing “the bara dance” they had invented out of absurd Bollywood moves. Whatever Soenil does, he always comes back home.

“I want to be true to myself,” he says. “You must never betray your own culture. That makes you unique. That can’t be copied.”

This attitude has cost him. It took many years to gain acceptance in the upper echelons of haute cuisine. The high priests of European culinary guides didn’t understand what he was doing or how to evaluate his dishes.

“I couldn’t be judged by traditional standards of French cooking,” he explains. “They couldn’t check my work against the Escoffier, the bible of haute cuisine. But what mattered to me was that I made pakoras with lobster. That was pioneering.”

At the beginning of his career, even getting a job in a kitchen was difficult for someone from his background. It took 60 applications for him to get one. This is why he now encourages people of all backgrounds and from anywhere in the world to apply for jobs in his own kitchen.

“I don’t care that you don’t know everything,” he says. “What matters is that you have the drive to want to know everything. I would like to give everyone the opportunity that I had to fight so hard to get.”

Some of the people he trained went on to get Michelin stars in restaurants of their own. And they, too, have incorporated elements of their own cultural backgrounds in their menus. Perhaps the phrase “Soenil revolution” isn’t so far-fetched after all.